CARTEL AND SYNDICATE EFFECT ON RICE MILL AND VEGETABLES:

Agriculture sector contributed about 27 percent in the GDP

with 14.38 percent AGDP shared by vegetables including potato (MOAD, 2017).

Vegetable production and marketing is gradually emerging as an important

sub-sector contributing to gross domestic product in Nepal. Vegetable

production and marketing is main source of income for the people of various

places in Nepal. However, the country is not able to harness available market

for vegetables, and different factors at production and marketing levels

hindering vegetable business. These vegetable marketers function in an

oligopolistic market structure with a relatively large number of counterpart

suppliers and buyers. These

are organized groups and have their own associations while their upstream and

downstream stakeholders in the supply chain do not have strong enough

associations to offset their unruly behavior.

Cartels have infested the milled rice, fruits

and vegetables, honey, meat and other subsectors in a big way making it

difficult to control access to markets for farmers. A cartel model of oligopoly

is a model that assumes that oligopolies act as if they were a monopoly and set

a price to maximize profit. Generally cartel is

understood as the arrangement among producers and suppliers of goods and

services to control the production, sales and price so as to restrict

competition and obtain monopoly or oligopoly in the market. Cartels may be

overt or covert as the producers and suppliers of goods and services can have a

tacit understanding or open agreement to fix the market price, allocate market,

increase prices and decrease the quality of the goods and services. Such practices are generally considered

as the worst forms of anti-competitive behavior and condemned by the laws of

various countries

.The ultimate effect of these anti-competitive practices is that the efficient

firms lose to the inefficient firms or suppliers as there are no incentives for

bringing down the cost and increasing the quality of goods and services. In

such a situation of duopoly or oligopoly, all the firms within the cartel

groups benefit by sharing the market without the need of improving efficiencies

in production or supply.

Hence,

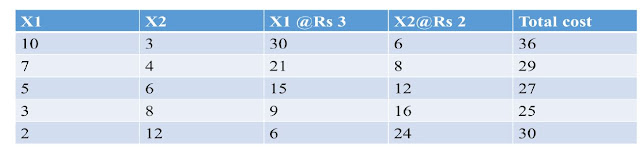

the farmers are fetching low prices on their products on the one hand and the

consumers are forced to pay higher prices at the other to the hefty benefit of

those middlemen. Middlemen have been involved in hoarding agricultural produce

in the past and in the process making it difficult for farmers to make money

out of their hard work. A market survey done at the Kalimati Vegetable Market

shows that the price paid by the consumers for some vegetable products are 10

times higher than the price paid by the middlemen to the farmers for the same

vegetables. This shows the intensity of unfair trade practices, much to the

chagrin of law enforcing authorities.

Cartel groups in Nepal are found in other

sectors as well. There are no organized (or wholesale) markets for the

collection of cereals and sale of processed grains. Millers based in major rice

producing districts directly sell their produce to wholesalers and retailers in

their areas after processing. The price of milled rice in the Terai regional

markets is determined by large local millers and traders. For example, there

are tacit understanding and clandestine agreements among the importers and

distributors of milled rice in order to fix price and control supply and raise

the price particularly during the festive season. Not much association is found

between the cost of production of rice and the market price, as price

determination is governed by local large millers and traders in the regional

Terai markets who determine the rice price considering the expected price in

Kathmandu and the price of paddy in the bordering Indian markets. These large

operators function in an oligopolistic market structure with a relatively large

number of counterpart suppliers and buyers. The lack of backward and forward

linkage markets can undermine trade flows, given the relatively small number of

stakeholders controlling the trade of cereals.

Competition is the cornerstone of open and liberalized

economy as the anti-competitive behavior of the enterprises, industries or

traders take a toll on the economic performances of a country by promoting

inefficient firms, producers and distributors and punishing the efficient ones. Perfect competition is an

ideal situation that is hard to achieve in any economy. However, it should be

the ultimate goal and direction to move forward which can be stepped upon by

gradually building on the legal, institutional and human resources base for

defying the anti-competitive behaviour. Reining the cartel requires

comprehensive and concerted approaches from all stakeholders and the

effectiveness of law enforcement agencies. The most important factor is the

requisition of political will and commitment to establish a competitive and

healthy market that could be the precursor to increased trade and foreign

direct investment in the country. Many developing countries including Nepal are

mired by the dilemma of politics protecting the cartels and syndicates as those

who are engaged in anti-competitive practices dole out substantial money to the

political parties and their leaders.

Cartels

effects have made farmers to drive away from the commercially viable

sub-sectors of agriculture. Groups of individuals who are out to make price

control and earning quick benefit from low quality products compared to high

quality goods must be dismantled under all costs. This must not be allowed to

happen, as the country wants to see more investments in agriculture especially

commercial vegetable and cereal production. Farmers must be allowed to make maximum

earnings from their investment especially given increased production and

rearing costs. The price of vegetable and rice should solely depend on demand

and supply situation in the market. The government must ensure that these

cartels and syndicates are dealt with immediately.

Comments

Post a Comment