Socioeconomic Factors Influencing Adoption of Improved

Maize Varieties in Nepal

S. Paudel*

Department of Agricultural

Economics

Institute of Agriculture and

Animal Science, Tribhuvan University

Kirtipur, Kathmandu

*samitapaudel2050@gmail.com

ABSTRACT:

This

article provides a review of different papers on adoption of improved maize

varieties in Nepal specifically on the factors that have the most significant

influence in adoption. The information was collected from the secondary data

available and analyzed. Several studies have pointed out a

number of socio-economic factors influencing the farmers’ adoption of improved

maize varieties. Among these factors, extension contact, education of household

head, farm size and off farm income are found to be major factors having strong

influences. Our study recommends the future studies on adoption of improved varieties

including perception of farmers.

Key words: Adoption,

Factors, Improved variety, Maize,

INTRODUCTION:

Maize

is the second most important crop after rice in terms of area (891,583 ha) and

production (2231517 t) in Nepal (MOAD, 2017). It is a main food crop of hill

farmers and main source of animal feed for feed industries in Terai region of

Nepal (KC et al., 2015). The annual demand of maize in the country is about

2.43 million mt. while its annual domestic supply is 2.15 million mt. (MOAD,

2015). During the year 2015 the average yield of maize was 2.4 t/ha, while

attainable yield for maize with available recommended varieties is about 5.7

t/ha (KC et al., 2015), this shows a huge yield gap. This high yield gap is due

to the unavailability of basic inputs like quality seed, fertilizer, irrigation

and technology augmented with the traditional production practices and poor

infrastructures. Nepal Agriculture Research Council has developed 30 varieties

of maize (NARC, 2016) and in addition, 34 imported hybrids of maize were

registered in Nepal (NMRP, 2013).The seed replacement rate for maize is 14.48%

which far below than recommended rate of 33 % for cross pollinated crops (SQCC,

2016).Improving the production of maize can be one of the important strategy

for maintaining food security and decreasing import situation in Nepal. It

would be a wise decision by farmers to adopt improved variety of maize, as

improved variety responds better to the inputs used and yields higher compared

to local. The adoption of high yielding crop varieties has been solution to the

lower production and lower income to the farmers in developing countries over

the years (Besley and Case, 1993).Kassie et al. (2012) reported that

agricultural technologies like improved seeds and inorganic fertilizers can

directly contribute in alleviation of food insecurity by improving crops

productivity for self-consumption and also for household income. However,

farmer’s decision on adoption of improved varieties is influenced by several factors

(Iqbal et al., 1999, Rogers, 2003). The main constraints hindering the maize

industry in Nepal are limited numbers of input suppliers, lack of proper

knowledge about improved varieties and technology, timely unavailability of

demanded inputs and inadequate education (Khatri-Chhetri, 2015).This research

is designed to determine the socioeconomic factors influencing the farmers’

decision to adopt improved maize varieties in Nepal. We expect this study will

help to identify the determinants of adoption of improved maize varieties by

farmers in developing countries. The study also aims to help policymakers to

introduce policies accordingly that would help to enhance adoption rates of

improve maize varieties and increase production and productivity.

OBJECTIVES:

Broad Objective:

Ø The

main objective of this study is to perform a systematic literature review about

the socioeconomic factors influencing adoption of improved maize varieties in

Nepal

Specific

Objective

Ø To

establish the extent to which age, gender and educational status of farmers

influences adoption of improved maize varieties

Ø To

determine the role of group membership influencing adoption of improved maize

varieties.

Ø To

determine how economic status of farmers influence adoption of improved maize

varieties

RESEARCH QUESTIONS:

This

study sought to answer the following questions:

1.

To what extent does age, gender and

educational status of farmers influence adoption of improved maize varieties?

2.

To what extent does the farmers’

involvement in cooperatives or group membership influence adoption of improved

maize varieties?

3.

How

does economic status of farmers’ influence adoption of improved maize

varieties?

REVIEW:

Adoption

of innovations refers to the decision to apply an innovation and to continue to

use it (Roger and shoemaker, 1971). The

adoption of new technologies, such as fertilizer, improved seed, etc. is

central to agricultural growth and increasing productivity. Although adoption

of new technology is an effective way to increase agriculture production and

productivity it is relatively complicate process. In the agricultural sector,

widening of adoption of new technology by all farmers is rare due to the

various deterrents to adoption imposed by various economic, social, physical,

and technical factors .There

are several socioeconomic factors influencing the rate of adoption, continuation

or discontinuation of new technologies in agriculture sector. Ghimire

and Huang (2015) found the positive influence between household wealth index

and adoption and intensity of adoption of improved maize varieties. The factors

most strongly related to adoption were farmers’ ages, with older farmers being less

likely to adopt, possibly because of risk aversion. Education and extension

services positively influenced adoption among poorly endowed households,

implying that increased awareness and information reduced risk aversion and

motivated farmers to adopt new technology. Similarly, Ransom et al. (2003)

found significant and positive relation between adoptions of improved maize

varieties with khet land area, ethnic group, years of fertilizer use, off-farm

income, and contact with extension. Extension services seem to have the biggest

impact on technology adoption as farmers who have

contacts with extension workers are more likely to hear about improved

varieties and thus adopt new agricultural technologies. Mishra et al. (2017)

reported household head, age of the household head, full time farm worker

Training Received or not, Farm Size, head Contact with extension agents, participation

in collective action, Source seed availability, Contact with processor were positively influencing adoption whereas, Distance

to market/road and off farm income were influencing negatively on adoption of

improved maize varieties. Similarly, Paudel and Matsuoka

(2008) found significant influences between winter maize cultivation, education

of the household head, lowland area, upland area as well as access to credit

and extension services with adoption of IMVs. Subedi et al. (2017) conducted a

survey on Socio-economic assessment on maize production and adoption of open

pollinated improved varieties in Dang, Nepal and reported that the adoption of

improved maize variety is determined by several factors like ethnicity, gender

of the household head, area under improved maize, number of visits by farmer to

agro vets and seed source. Among the variables ethnicity, area under IMVs and

extension service were found highly positively influencing compared to others.

METHODOLOGY:

The

study is based on the secondary information collected by reviewing different

published journal articles and proceedings. The papers were mainly based on

factors affecting adoption and continuation of improved maize varieties by

farmers of Nepal and developing countries. Several parameters were found

influencing the farmers’ adoption behaviour of improved maize varieties. The

research of social scientists have accumulated the various demographic and

socioeconomic factors behind the adoption behaviour of farmers like age,

gender, education, distance from market, availability of credit, information

sources, extension services, knowledge, awareness, attitude, and involvement in

cooperatives or group.

DISCUSSION:

In

this review we found eleven major socioeconomic

factors influencing significantly on the farmers’ adoption of improved maize

varieties. The list includes age, gender, and education, farm size, off farm

income, extension contact, and access to credit, group membership and marketing

distance.

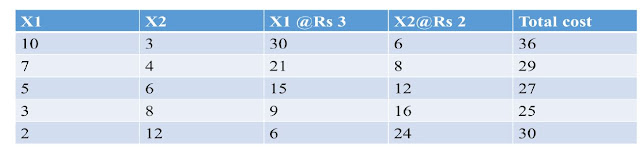

Table 1. Factor estimates

of adoption of improved maize varieties.

|

S.N.

|

Variables

|

Studied

|

Positive

|

Negative

|

|

1

|

Age

|

2

|

|

*

|

|

2

|

Gender (Female)

|

3

|

*

|

*

|

|

3

|

Education (House hold

head)

|

4

|

*

|

|

|

4

|

Farm size (land size)

|

4

|

*

|

|

|

5

|

Off farm income

|

4

|

*

|

|

|

6

|

Extension contact

|

5

|

*

|

|

|

7

|

Access to credit

|

2

|

*

|

|

|

8

|

Group membership (Cooperatives)

|

2

|

*

|

|

|

9

|

Marketing distance

|

1

|

|

*

|

|

10

|

Ethnicity (Brahmin/Chettri)

|

2

|

*

|

|

|

11

|

Household wealth

|

1

|

*

|

|

The

age of household head happens to be one of the human characteristics that have

been frequently associated with non-adoption of IMV in many adoption studies (Ghimire and Huang, 2015), (Paudel and Matsuoka, 2008).

The older farmers are reluctant to adoption of IMVs than younger which is due

to the fact that the younger people have greater exposure to new technologies

and ideas and have more risk bearing capacity.

The

gender of household head being female was found to be positively influencing

the adoption of improved maize varieties in several studies (Subedi et al.,

2017), (Ghimire and Huang, 2015) while

this result contrasts with Kafle and Shah (2012) reported that the male headed

household positive influences on the adoption of hybrid maize varieties than

others. The reason behind the female household head adopting IMVs is also the

government encouragement of women participation and gender inclusion in various

programmes (Ghimire and Huang, 2015).

Education

was found positive and significant in a large number of adoption studies. (Ghimire and Huang, 2015) reported that the one

additional increase in year of education of household head was found increasing

the probability of adopting IMVs by 2 %, the reason behind this is that educated

farmers have better information and risk bearing capacity than less educated

ones. This result is supported by previous literature (Paudel and Matsuoka,

2008) suggesting that adoption depends on the decision makers’ educational

level and access to information because education is thought to create a

favorable mental attitude for the acceptance of new practices. However (Mishra

et al., 2017) found no significant influence of education of house hold head in

adoption of improved maize variety.

Farm size had a positive and significant

influence on the probability of adopting IMVs in several studies. Ransom et al.

(2003) reported that every 1 ha increase in Khet land area would increase the

adoption of improved maize varieties by 13.5%.It was supported by (Ghimire and Huang, 2015) and (Subedi et al.,

2017). However Mishra et al. (2017) reported that the larger land holding size

has negative contribution in adoption of maize seed production as they have

other options to grow more profitable cash crops, and they are generally food

secure and look for off farm employment. The availability of extension services

plays important role in increasing likelihood of adopting IMVs (Ghimire and Huang, 2015).This result is supported

by Paudel and Matsuoka (2008) and Ransom et al. (2003) that farmers having

contacts with extension workers are more likely to hear about improved

varieties and thus have more incentive to adopt new agricultural technologies Ghimire and Huang (2015) found that the greater

the participation of farmers in groups/cooperatives, the more likely they were

to adopt IMVs. Similar findings were found by Sharma and Kumar (2000), this

result shows that farmers’

exposure

to various information sources is associated with the advantage of new

innovations and ability to take risk.

Ghimire and Huang (2015) reported that the distance

from market appeared to have a negative influence on the adoption of IMVs among

poorly endowed households. Similar result was reported by Mishra et al. (2017)

that higher the distance from nearest market center there is difficulty in

input and output transportation, and higher transportation cost limits the

adoption of improved variety maize seed production. However (Ransom et

al.,2003) found out that in remote villages adoption of fertilizer is higher

than the adoption improved seed though seed is relatively cheaper the poor

adoption of IMV seed cannot be blamed for longer distance from market (Ransom et al,.2003).

The

large changes in off-farm income has a positive influence on adoption of

improved open pollinated maize varieties. With the increase in every 1000 Rs.

increase in off-farm income would increase the adoption of improved open

pollinated maize varieties by 0.2% (Ransom et al., 2003).It is a fact that

farmers with large off-farm income have increased cash in the family and they

will be able to purchase required inputs. Similar findings were reported by (Ghimire and Huang, 2015).However, (Mishra et

al., 2017) found households with higher income from nonfarm business and off

farm employment are less likely to adopt improved variety maize seed

production. As agriculture is a labour intensive and less profitable business

compared to others, people with higher off farm income g are not interested in

adoption of improved maize varieties. Ransom et al. (2003) reported that credit

facility is one of the important factor influencing the adoption of improved

maize varieties by the farmers. This was supported by Paudel and Matsuoka (2008).The

house hold wealth is another important factor influencing the adoption of

improved maize varieties. Wealthier the households more willing to adopt

improved maize varieties as they have better ability to cope with production

and price risks (Ghimire and Huang, 2015).

The role of ethnicity also seems influencing on adoption of improved maize

varieties. Brahmin/Chettri ethnic group was found to be positively related to

the adoption of improved maize varieties as compared to other ethnic groups

(Subedi et al., 2017).

CONCLUSION:

The

main purpose of this review was to examine socio-economic factors influencing

adoption of improved maize varieties in Nepal. The socioeconomic characters

that were included were age, gender, education, farm size, offfarm income,

extension contact, access to credit, group membership and distance from market.

The adoption study needs location and technology specific study since the same

factor may be influencing the adoption of maize varieties in different way in

different places. However, from the result we can conclude that the extension

contact, education of household head, farm size and off farm income are the

major factors determining the adoption of improved maize varieties. The farmers’

perception of higher yield and profitability in IMV should be highlighted

through extension agents and information sources to enhance the adoption rate

of IMV. Researchers are also suggested to study the influences of communication

channels and farmers’ perception on adoption of agricultural innovation which

are equally important to the socio-economic variables.

Besley,

T. and A.Case.1993. Modeling technology adoption in developing countries. The

American Economic Review. 83(2).pp.396–402.doi: 10.2307/2117697.

Ghimire, R. and W.C.Huang. 2015.

Household wealth and adoption of improved maize varieties in Nepal: a

double-hurdle approach. Food Security, 7(6). pp.1321-1335. doi:

10.1007/s12571-015-0518-x

Kassie,

M., M. Jaleta., B. Shiferaw., F. Mmbando and H. Groote De.2012.Improved Maize

Technologies and Welfare Outcomes In Smallholder Systems: Evidence From

Application of Parametric and Non-Parametric Approaches. Selected Paper IAAE

Triennial Conference, Foz do Iguaçu, Brazil, 18–24 August 2012.

KC, G., T.B.Karki., J.Shrestha, and B.B.Achhami.2015.

Status and prospects of maize research in Nepal. Journal of Maize Research and

Development.1 (1).pp.1-9.

Khatri-Chhetri,

D.2015. Maize seed value chains in the Hills of Nepal- Linking small farmers to

markets. Paper presented at Regional Workshop on Agricultural Transformation:

Challenges and Opportunities in South Asia, Kathmandu, Nepal, February 13,

2015.

Mishra, R. P., G.R. Joshi and Dilli KC.2017. Adoption

of improved variety maize seed production among rural farm households of

western Nepal. International Journal of Agriculture Innovations and Research.

6(2), 2319-1473.pp.423-431

MOAD.2015.

Statistical Information on Nepalese Agriculture. Government of Nepal, Ministry

of Agriculture Development, Singhdurbar, Kathmandu Nepal.

MOAD.2017. Statistical Information on Nepalese

Agriculture, Government of Nepal, Ministry of Agricultural Development,

Singhdurbar, Kathmandu Nepal.

NARC.2016. Newly Released Crop Varieties. Published by

Government of Nepal/ Nepal Agriculture Research Council,

http://www.narc.gov.np/narc/varieties_released.php (accessed on 24th October,

2016).

NMRP.2013.

Registered maize Varieties in Nepal Up to 2013. Published by Government of

Nepal/ Nepal Agriculture Research Council/National maize Research Program,

Rampur, Chitwan.

Paudel, P. and A. Matsuoka.2008.Factors influencing of

improved maize varieties in Nepal: A case study of Chitwan district. Australian

Journal of Basic and Applied Sciences. 2(4).pp.823-834.

Ransom, JK., K. Paudyal and K. Adhikari.2003.Adoption of improved

maize varieties in the hills of Nepal. Journal of the International Association

of Agricultural Economics, 29(3).pp.299-305.

Rogers, E.M. and Shoemaker.1971.Communication of

innovations: A cross culture approach. The Free Press, Collier Macmillan

publishing Inc. NY. Pp.11-28.

Sharma, V. P.and A. Kumar.2000. Factors influencing adoption of

agroforestry programme: a case study from North-West India. Indian Journal of

Agricultural Economics, 55(3).pp.500–510.

SQCC.2016.

National Seed Balance Sheet. Seed Quality Control Center (SQCC), Ministry of

Agriculture Development (MOAD) Pulchowk Lalitpur Nepal.

Subedi, Sanjiv., Yuga Nath Ghimire and Deepa

Devkota.2017. Socio-economic assessment on maize production and adoption of

open pollinated improved varieties in Dang, Nepal. Journal of Maize Research

and Development. 3 (1).pp.17-27 DOI:http://dx.doi.org/10.3126/jmrd.v3i1.18916

Comments

Post a Comment